The story of how an eight minute film about a lonely astronaut who decides not to return home took thirteen years to get made

On September the 11th 2001 in New York City, an airplane flew into the twin towers. The buildings burned and people were jumping out of windows to their death. Everything was covered in a thick layer of white ash. The world had become a pit of despairing disillusionment and America was in a neon doghouse. It felt like the end of a big bad beautiful and ultimately deceptive and violently abusive relationship. I couldn't stop thinking about it.

I Couldn’t Stop Thinking About It.

I had been doing a heavy spate of late 60s early 70s Sci Fi, stories of men trapped in space, lonely depressed men in peril. I became obsessed with the astronauts wives, waiting patiently back home on Earth, trying desperately to remain calm and strong for the children, for the country, for their lonely depressed husbands trapped in space.

In 2004 a melody motif was plucked from a Yamaha SY77 towards the end of an unproductive studio session. It sent me off down a rabbit hole of feeling the loss that comes from failing to communicate important things; or be heard. I wrote Lost In Space in two hours. A short play about a satellite fix it guy who has an emotional breakdown on the job and decides not to return home. I called him Larry. The next day I recorded a blue print for the voices and with my sound production partner Jack Henney (Cargo77), we assembled all the sound particles. I wanted it to feel like a warm, supportive hand on the shoulder when the ship is going down and you need a strong friend. Not too cute. Not too sad. Just present.

I asked Rufus Dean, a close childhood friend to play the parts of both Jim and Joe the jaded ground control. Later on he would become the 70s Italian soft porn voice of Radiostudio79. I wrote a handwritten letter to Jack Henney's dad, Del Henney, asking if he would consider playing the part of Larry's father. Del Henney is best known for playing Colonel Archer in Docter Who's Resurrection Of The Daleks and his role as Charlie Venner, the rapist in Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971). I was extremely pleased he agreed to do it. I voiced both the parts of Larry's abandoned wife and the ships sentient intelligence system.

It took six weeks to get to a point where we both felt it was a completed piece of audio work. Then it just sat there. It sat there for ten years. Not quite knowing if it belonged anywhere. I moved in with a french guy. I moved out. I fell in love with a musician. I cried a lot. I turned forty. I drank too much. Sometimes I would play it for guests who had come for dinner. Where was Larry?

“Does your allegiance to The United States Of America mean anything to you anymore Larry? ...Larry?”

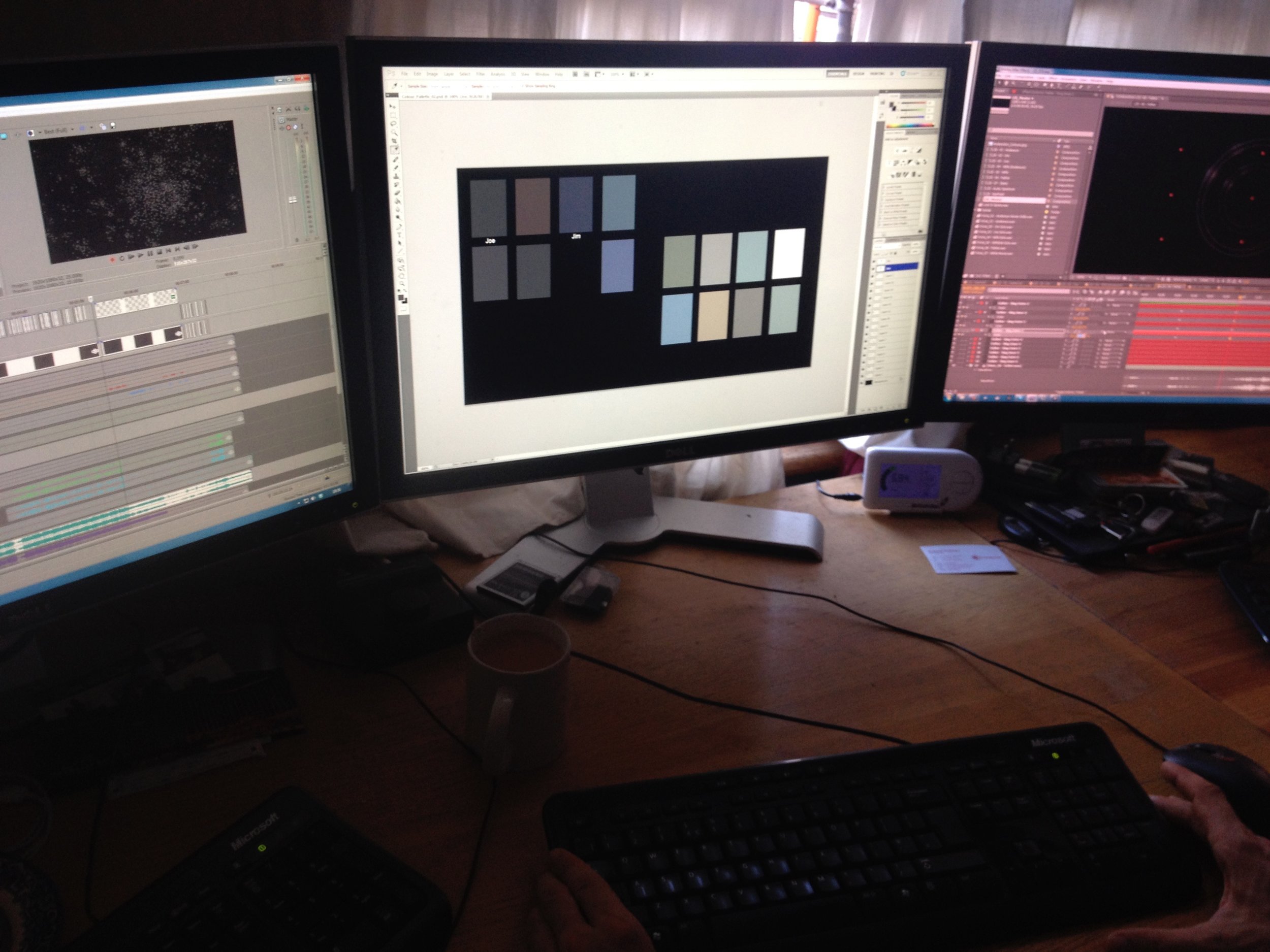

In the summer of 2014 The Tate commissioned me to make it into a film so that it could be presented as an audio visual piece. I knew I wanted it to be an animation but I had absolutely no idea how to even talk the language so I called a techy friend, Phillip Mayer, builder of domes, to ask if he wanted to make a film with me for Tate Britain. He said he would. Then I told him we had six weeks to complete. He said we could try.

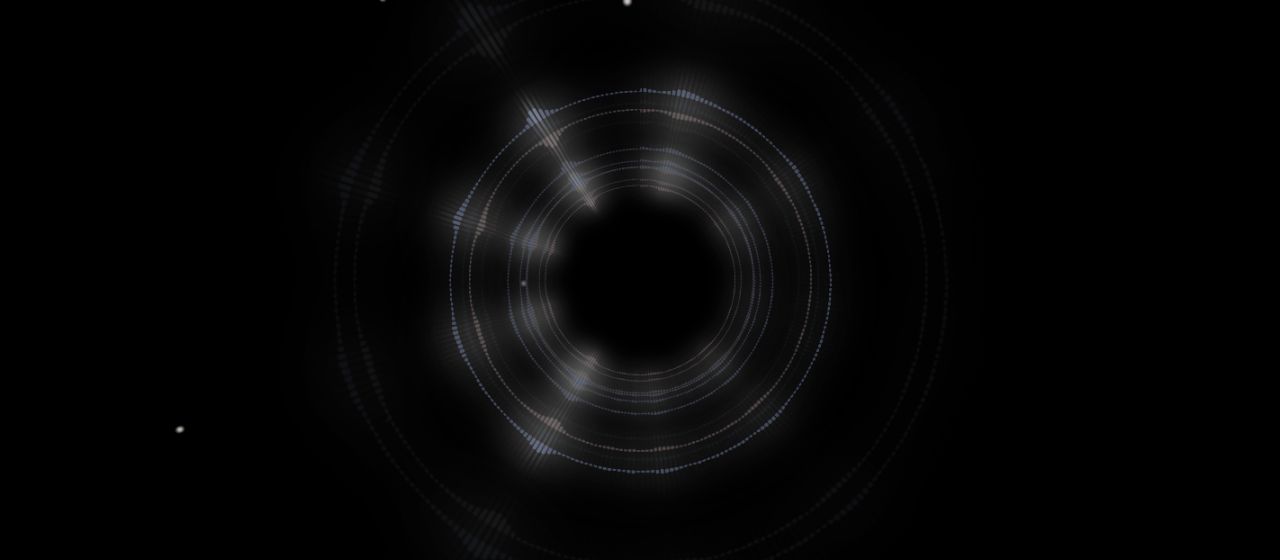

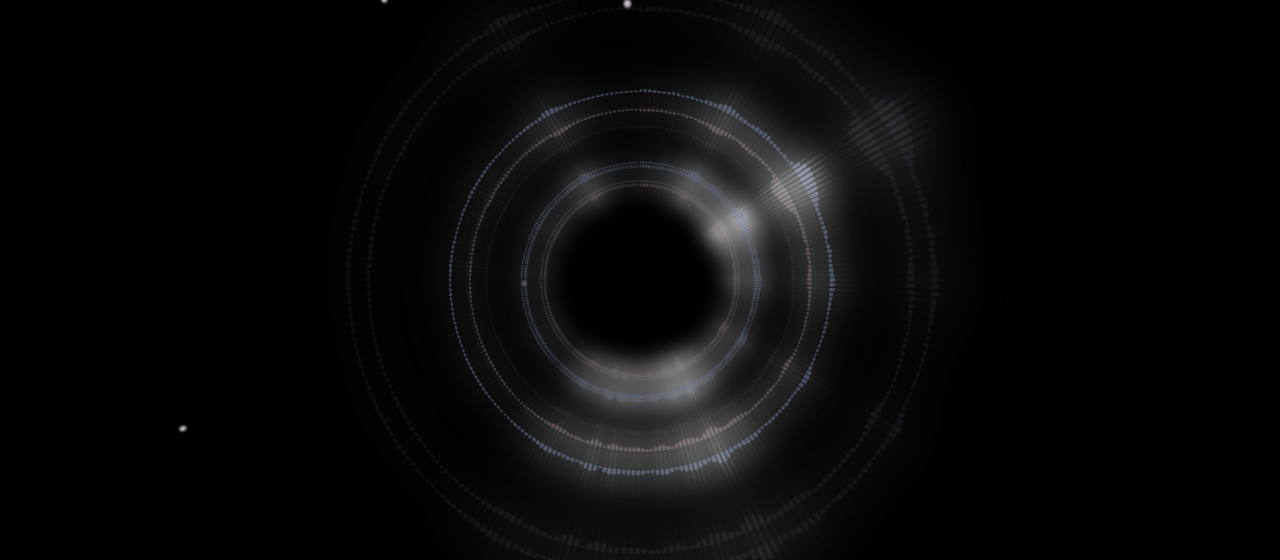

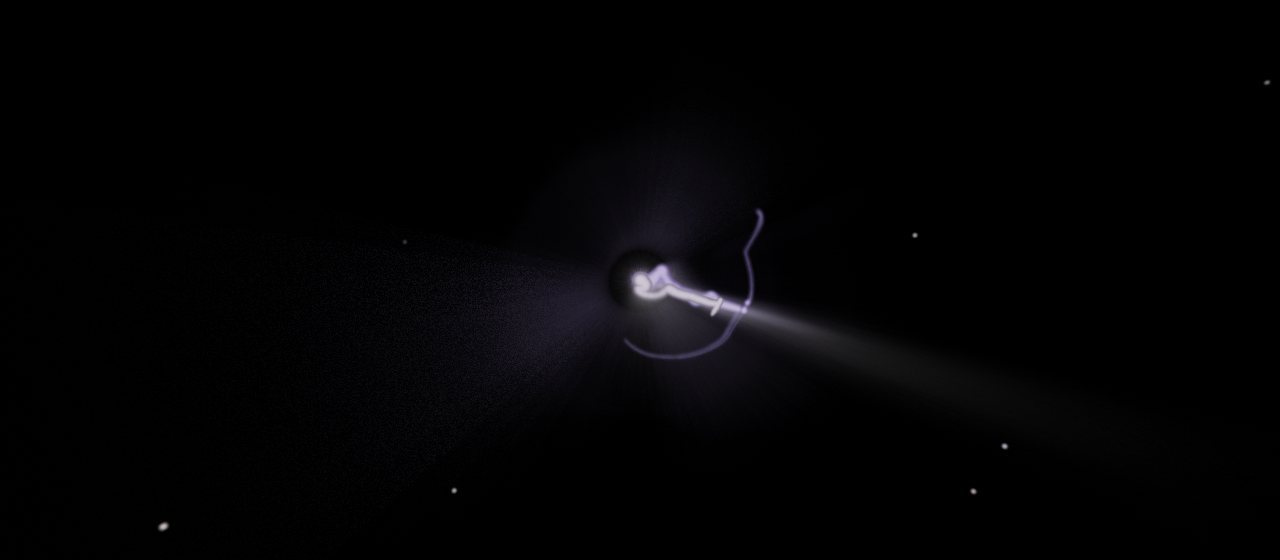

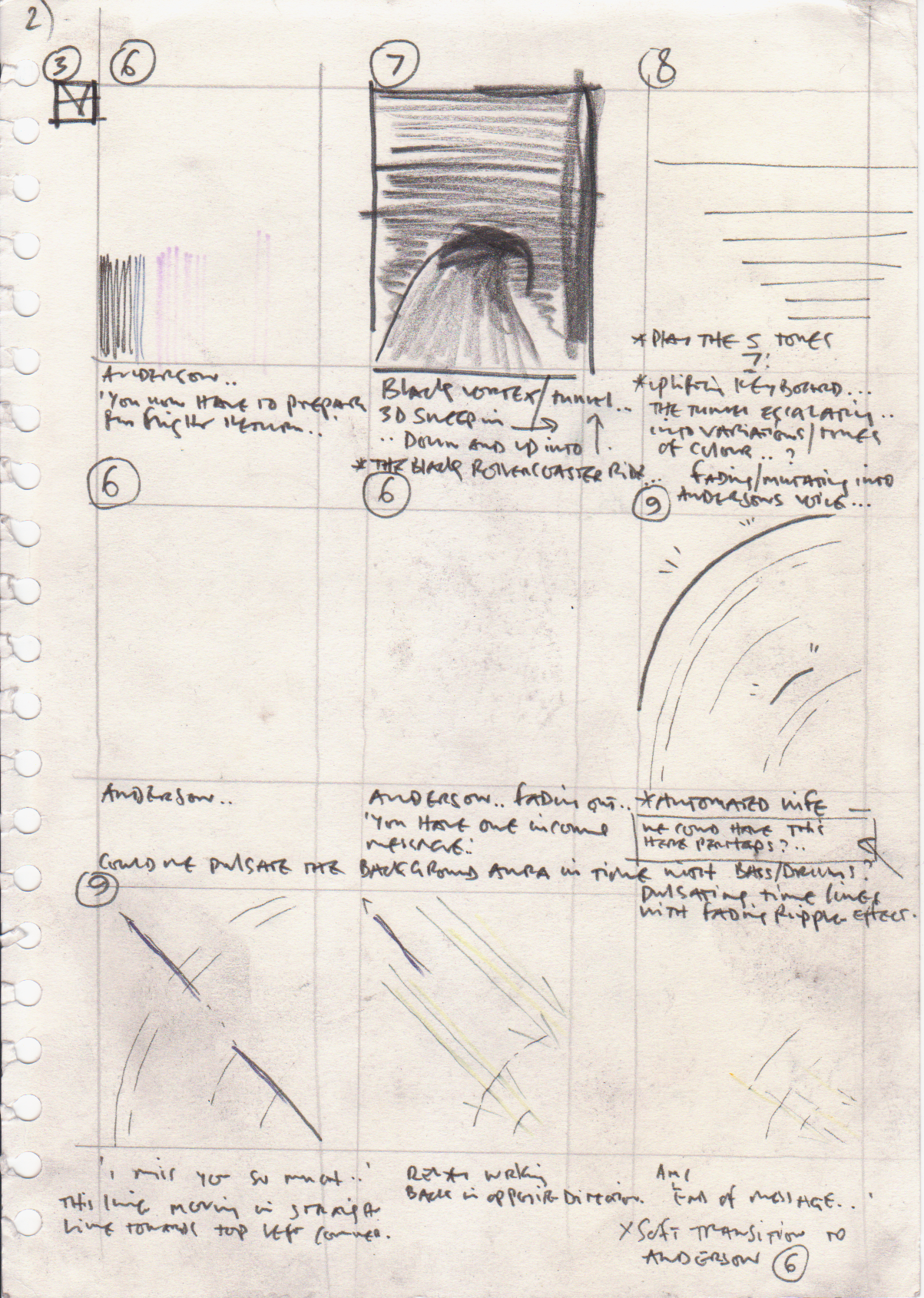

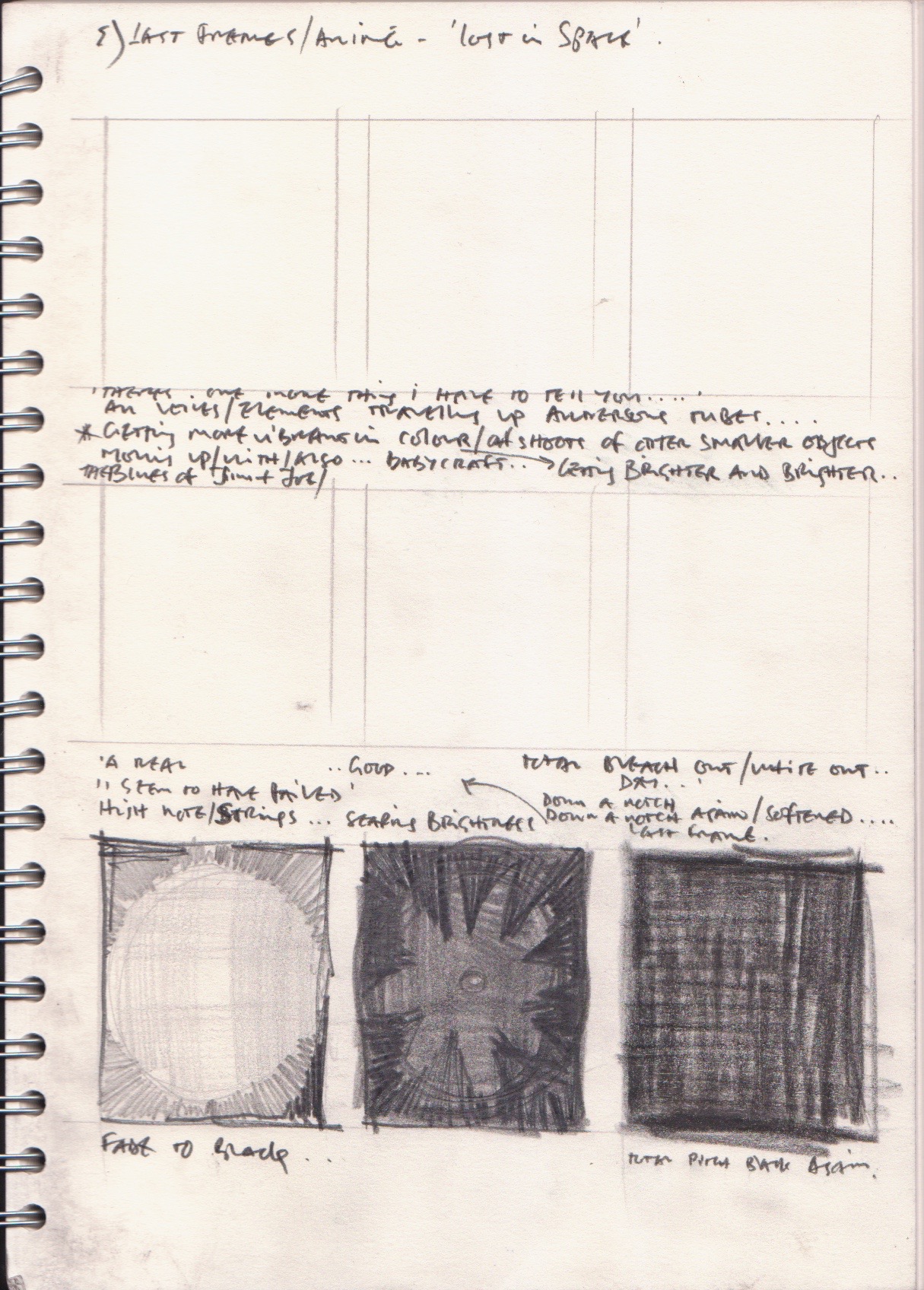

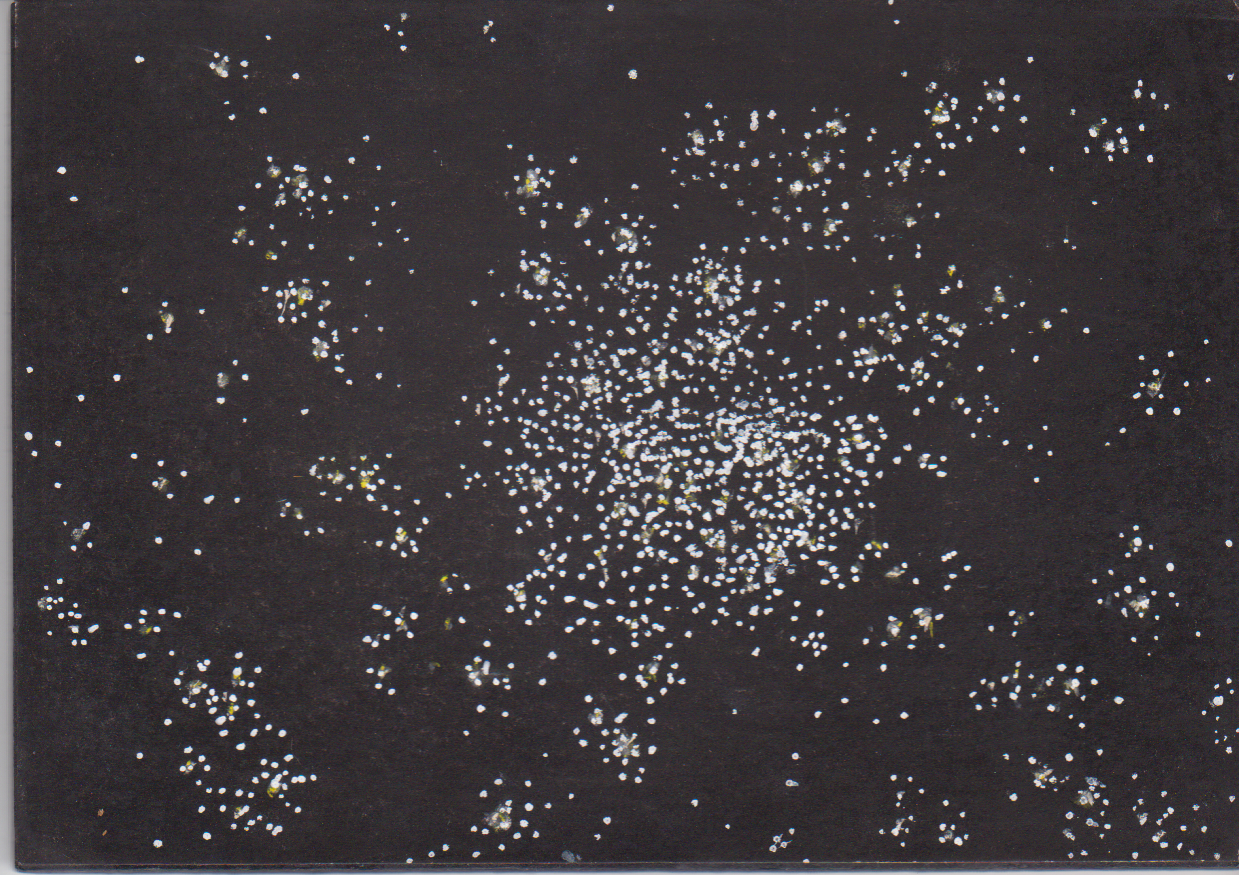

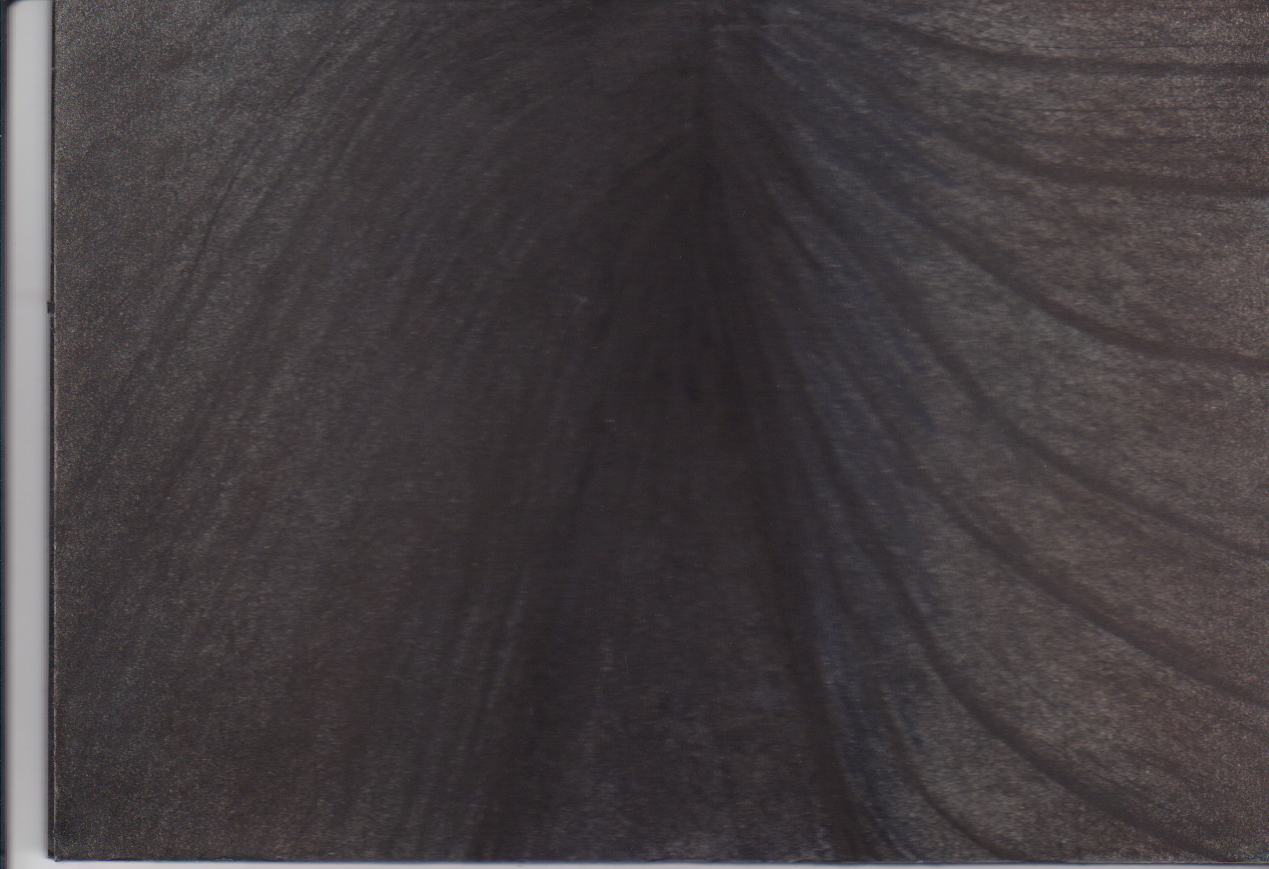

I had a collection of moving and still images, a mishmash of oil slicks, auroras and 90s pop videos. We created a colour chart and experimented with movement and texture. I wanted each character to have their own colour, form and movement style. Initially it all got a bit Tron. It ended up clunky and completely missing the tunnel sequence, the journey into Larry's mind as his father is speaking. I wanted to lead the audience into a personal experience of the devastating effect this has on him. In my mind the final sequence was a cacophony of all of the elements melting into one-another and becoming an all encompassing mandala which would then blow like an atom device, destroying everything in order for a phoenix to rise from the ashes. It wasn't the dream but we had a film. Duncan Jones made Moon. I felt happy.

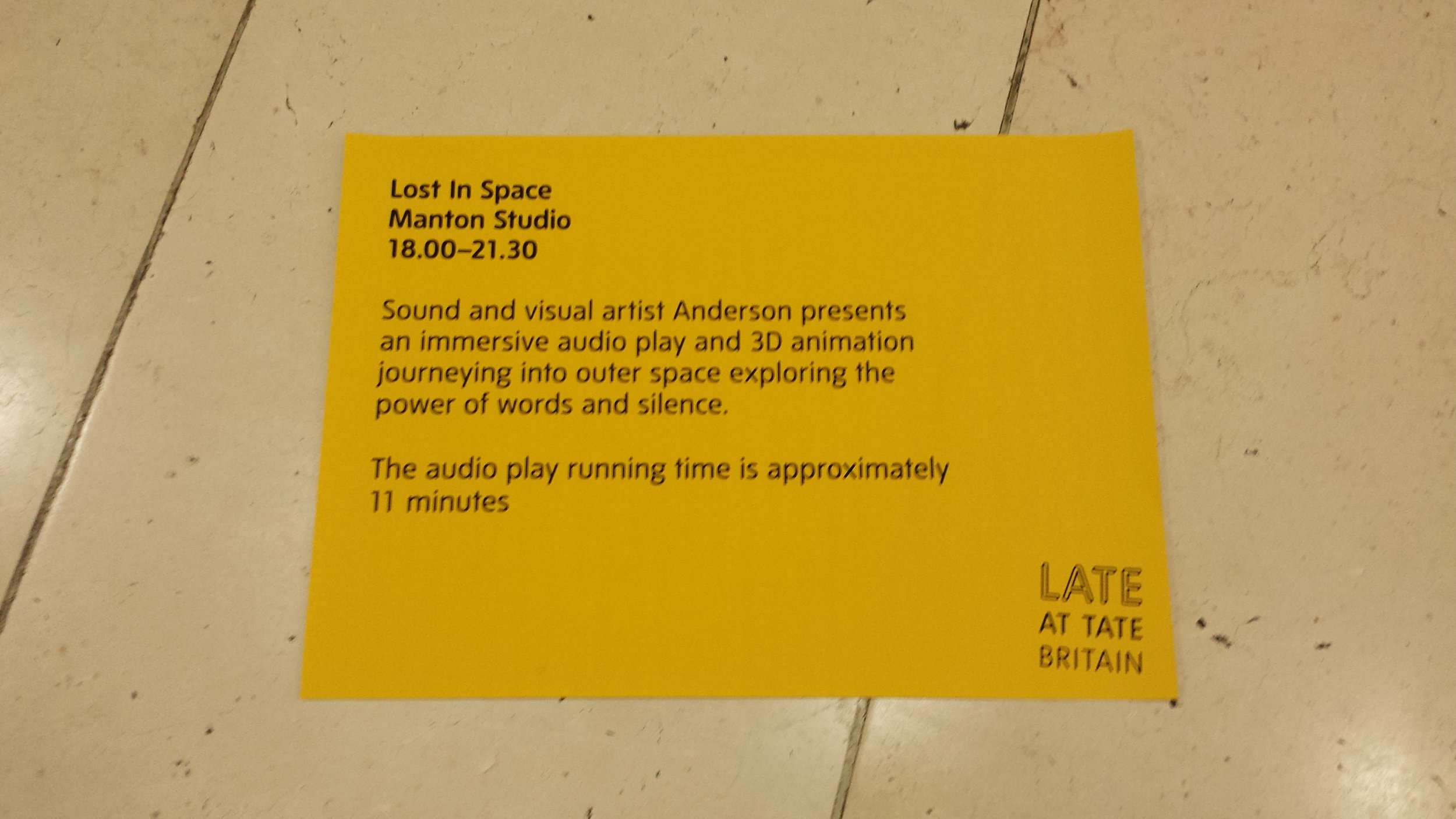

Lost In Space was shown at Tate Britain as part of Late At Tate - Spaces Between in August 2014.

ANDERSON, Winter 2017